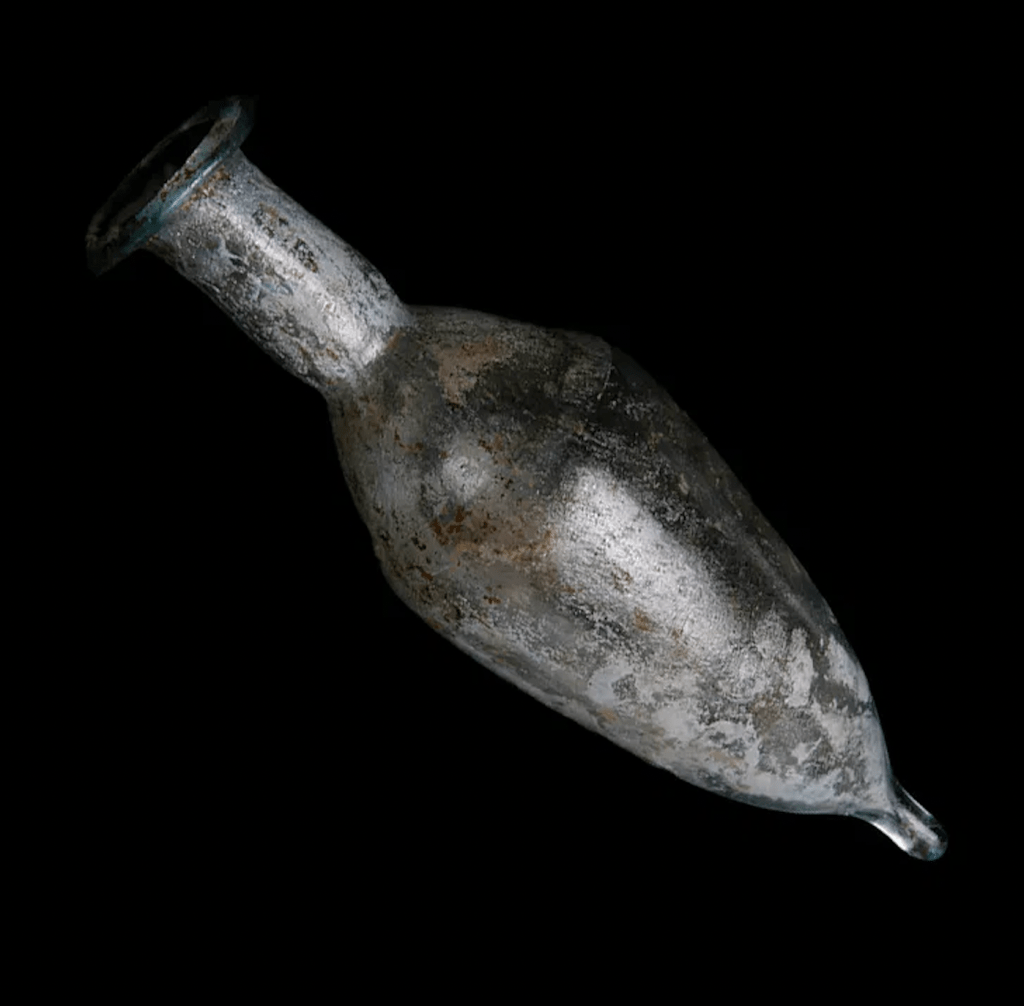

Date: Circa 1st–2nd Century AD More information: https://www.ancient-art.co.uk/roman-empire/ancient-roman-glass-perfume-bottle/

“Wendy, you smell like an Egyptian whore house”. I vividly remember my mom telling me about this encounter with her Dad and being perplexed about two things: how did he know what it smelt like, and then why did that smell mean something so specific? As an adult this leads me to think about the significance of smells, the meanings we give them, and how this relates to our performance of gender. As human beings our relationship to scent encompasses morality, ‘race’, class, gender and the ontology of being. By utilising the work of Mark Graham on scent and materiality and Judith Butler on performativity I hope to explore the ontology of scent and its connection to gender through a neo-materialist feminist perspective. I will also look at several sociological perspectives on the history of scent and several perfume ads to better understand our relationship to scent and our experience of becoming as human beings when we use scent to change who we are and how others see us.

In order to adequately examine the importance of scent as a tool of performativity we need to identify the relationship of scent to us as human beings and its ability to construct our reality. In Undoing Gender, Butler (2004) discusses this idea saying that examining gender performativity allows us to “grasp one of the mechanisms by which reality is reproduced and altered in the course of that reproduction.” (Butler, 2004, p.218). When looking at the cartesian relationship of the mind and matter Graham (2020) discusses the need for us as human beings to fix or freeze complex processes of ‘being’ in order to comprehend and interact with, or apply them to, our lived existence. However they also state, “in doing so we miss something about the fluidity and openness of objects in the process, their thingness or otherness.” (Graham, 2020, p.88). This fluidity could be explained by applying Rebecca Coleman’s work on the becoming of bodies (2008), “Becomings are transformations- not of forms transforming into another or different form but of continual processual, constantly transforming relationships.” (Coleman, 2008, ND). Essentially scent is not just something I use but it is also something that acts upon me and I react to. By moving from a classical perception of reality as something that ‘is’, and is therefore categorizable and fixed, to one that is a “mutual imbrication of mind and matter” we can use a neo-materialist approach to analyse scent as becoming rather than simply being. (Graham, 2020, pp. 87-89; Rossini, 2006). This centrality of scent as a building block of our reality emphasises its importance to us as a powerful tool of performativity in society.

In their article on the sociology of odor Largey and Watson (1972) discuss the link between morality and odor by reviewing the historical context of scent. From fiction to common misbeliefs rooted in racism and xenophobia the positioning of smell to social status, moral character, and hygiene is inextricably linked to narrative discourses around who we are, how we define ourselves, and our relationship to those who are othered. Historically scent has been used to other entire collectives. However the more modern approach has been centered on an imitation of the biological function of scent, in particular pheromones, which render us, “favourably to some and unfavourably to others.” (Burton, 2015, p.31). The effect of this, I would argue, created a gap in the market and an incentive to cultivate and spread somatophobia by communicating the need to alter our presentation of scent. For example Largey and Watson (1972) discuss the presentation of, “an olfactory identity that will be in accord with societal expectations, in turn gaining moral accreditation: he who smells good is good.” (Largey and Watson, 1972, p.1028). By situating scent as a character reference it allows us to see the regulatory behavior of scent in action and how it specifically can impact gender.

This relates to the idea that some scents are ‘naturally feminine’ and some are ‘naturally masculine’ stemming from historical associations which position scent as gender essentialist. For example, traditionally floral scents are closely aligned with the ‘feminine’ as flowers have been related to the feminine in art, music, and literature for thousands of years (Largey & Watson, 1972; Stott, 1992; Marc Jacobs, 2020; Lancôme Fragrances, 2020). The traditionally masculine smell is more difficult to define and seems to be based less on a particular smell and more on how it is perceived by the person you are trying to attract (Old Spice, 2010). An article in Vogue (2013) touches on the simplicity strived for when creating the ‘masculine smell’, “masculine, powerful, and clean” (Vogue, 2013; Giorgio Armani Fragrances, 2020). It is important to note that we can see a male-in-the-head approach to scent here particularly when discussing who is an active actor and who is the passive receiver, “Women have to be chosen by a man, while men have to be accepted by a woman” (Holland, 2008; Vogue, 2013). The more modern trend in scent is a gender fluid approach which is fast becoming mainstream with multiple scents no longer using gender as a label or marketing technique but rather the opposite, showing a diverse and intersectional group of people in the advertisements for it. (Kate Moss Vidéos, 2016; Valentino Fragrances, 2020). In their article on gender fluidity as a luxury, McIntyre (2019) argues that luxury companies have identified a new, more socially conscious audience and have begun to cater to their desires. This change of marketing describes gender fluidity, and also freedom from social constructs for women, as a luxury in and of itself resulting in, “a commodification of gender fluidity rather than the dissolution of gender categories.” (McIntyre, 2019, ND).

The fetishisation of identities or ethical frameworks is not new when interacting with capitalism nor is the co-opting of choice feminism as a false affirmation of choice within gender stereotypes, as demonstrated in the ‘Good Girl’ perfume ad for example (Carolina Herrera Fragrances, 2020; Mackay, 2015). On the other hand the traditional approach of a more distinct gendering of scent reinforces a binary view of gender and the stereotypes that come with it. The power of societal discourse to produce and reproduce our performances is emphasized by Mary Evans (2003) who states, “all gendered behavior is a matter of the internalization of social expectations.” (Evans, 2003, P.57). By acknowledging the power of scent to create our lived experience as a performative tool we can reveal another, less talked about, element of what society defines as an ideal type of ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ that is used to regulate our societal discourses.

References:

Burton, L. (2015) ‘Swallowable Parfum’: The Evolution of Scent or the Senses? In: Downing Peters, L. ed. (2000) The Body Beautiful? Identity Performance, Fashion and the Contemporary Female Body. [online]. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, pp. 29-48.

Available From: https://www.academia.edu/14477333/Swallowable_Parfum_The_Evolution_of_Scent_or_the_Senses [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Butler, J. (2004) Undoing Gender [online]. Oxfordshire: Routledge. Available From: https://www.vlebooks.com/Vleweb/Product/Index/136138?page=0 [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Carolina Herrera Fragrances. (2020) Carolina Herrera Good Girl TV Commercial, ‘Official: Fantastic Pink’ Ft. Karlie Kloss, Song by Chris Issak. iSpot.tv . Unknown Publishing Date. Available From: https://www.ispot.tv/ad/nto3/carolina-herrera-good-girl-official-fantastic-pink-ft-karlie-kloss-song-by-chris-issak

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

Coleman, R. (2008) The Becoming of Bodies: Girls, media effects, and body image. Feminist Media Studies [online]. 8 (2), pp. 163-179. Available From:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14680770801980547?scroll=top&needAccess=true [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Evans, M. (2003) Gender and Social Theory. Buckingham: Open University Press

Giorgio Armani Fragrances. (2020) Giorgio Armani Acqua di Giò Profundo TV Commercial, ‘A New Intensity’, Song by KALEO. iSpot.tv . Unknown Publishing Date. Available From: https://www.ispot.tv/ad/tfc7/giorgio-armani-acqua-di-gi-profondo-a-new-intensity-song-by-kaleo

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

Graham, M. (2020) Materiality. Lambda Nordica [Online]. 25 (1), pp. 87-91. Available From: https://search.proquest.com/openview/6862831e49cfabdfda10387191bf3628/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=4758914 [Accessed 7 December, 2020].

Holland, J. (1998) The male in the head: young people, heterosexuality and power [Online]. London: Tuffnell Press, pp. 26-42. Available From: https://content.talisaspire.com/uwe/bundles/5d9eea7bc1af242a3e2495c4

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

Kate Moss Vidéos. (2016) CK One Commercial 1994. YouTube . 14 March. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtE0-7wDjM0 [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Lancôme Fragrances. (2020) Lancôme La Vie Est La Belle TV Commercial, ‘Expression’ Featuring Julia Roberts. iSpot.tv . Unknown Publishing Date. Available From: https://www.ispot.tv/ad/nObP/lancme-la-vie-est-belle-expression-featuring-julia-roberts

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

Largey, G.P., Watson, D.R. (1972) The Sociology of Odors. American Journal of Sociology [online]. 77 (6), pp. 1021-1034.

Available From: https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/stable/2776218?pq-origsite=summon&seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

Mackay, F. (2015) The biggest threat to feminism? It’s not just the patriarchy. The Guardian [online] 23 March. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/mar/23/threat-feminism-patriarchy-male-supremacy-dating-makeup [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Marc Jacobs. (2020) Marc Jacobs Daisy TV Commercial, ‘Field of Flowers’, Featuring Kaia Gerber, Song by Suicide. iSpot.tv . Unknown Publishing Date. Available From: https://www.ispot.tv/ad/nI3x/marc-jacobs-daisy-field-of-flowers-featuring-kaia-gerber-song-by-suicide

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

McIntyre, M.P. (2019) Gender fluidity as luxury in perfume packaging. Fashion, Style, & Popular Culture [online]. 6 (3), pp. 389-405. Available From: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/fspc/2019/00000006/00000003/art00006 [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Old Spice. (2010) Old Spice| The Man Your Man Could Smell Like. YouTube . 4 February. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owGykVbfgUE [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Rossini, M. (2006) To the Dogs: Companion Speciesism and the new feminist materialism. Kritikos: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal of Postmodern Cultural Sound, Text and Image [online]. 3, pp. 1-27. Available From: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254870797_To_the_Dogs_Companion_speciesism_and_the_new_feminist_materialism [Accessed 15 December].

Stott, A. (1992) Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition. American Art [online]. 6 (2), pp. 60-77. Available From: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3109092?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[Accessed 7 December 2020].

Valentino Fragrances. (2020) Valentino Voce Viva TV Commercial, ‘The New Fragrance’ Featuring Lady Gaga, Song by Lady Gaga, Elton John. iSpot.tv . Unknown Publishing Date. Available From: https://www.ispot.tv/ad/n9zA/valentino-fragrances-voce-viva-the-new-fragrance-featuring-lady-gaga-song-by-lady-gaga-elton-john [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Vogue (2013) Perfect Chemistry: How Women Want Men To Smell. Available from: https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/perfect-chemistry-how-women-want-men-to-smell [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Second Year Undergrad