“[T]he overt ‘signs’ of race.. in video games are epiphenomenal on-screen symptoms of far more entrenched racial fictions encoded within.”

FICKLE, 2019, P.2

The dialectical relationship between society and the simulation of video games allows paradigms of racism to be grafted onto alien worlds with alternate races and socio-economic strifes. This report is limited by the research available which primarily focuses on ‘race’ within the US video game market and therefore focuses on the issues of ‘race’ and racism within a western context rather than global. To look at video games holistically, within this context, it is important to acknowledge both the community aspects of gaming as well as the games themselves. This extends to the social spaces of gaming chat, YouTube commentary and let’s plays, as well as review/comment forums on purchase spaces such as Steam, Green Man Gaming, Epic Games etc. However, research in this area is limited so a wider approach to sociological research on ‘race’ within institutions was used. As such, this report will focus on the transferal of systemic racism from western social reality and narratives to a virtual reality, what enables this, and how it could be addressed.

Section 2: The Theoretical and Conceptual Context

What is systemic racism?

In order to situate the construction of racism in video games it is important to first point to the social construction of ‘race’ itself. Winant (2000) identifies the modern and most realised definition of ‘race’, as of the Middle Ages, to be, “a concept that signifies and symbolizes sociopolitical conflicts and interests in reference to different types of human bodies.” (Winant, 2000, p.172). When establishing their racial formation theory Omi and Winant (1994) make it clear that no social category can rise to the solidified position of a fixed and objective social fact, but they do elucidate the life cycle of racial categories by looking at how they are, “created, inhabited, transformed and destroyed.” (Omi and Winant, 1994, p.55). Their theory of racial formation does have limitations when it comes to its ability to explain the consistency and power of ideas on ‘race’ and racism and their perpetuation through structures within society. In order to identify and lay bare these structures it is helpful to examine how societal institutions are produced.

“[R]ace and races are products of social thought and relations”

Delgado and Stefancic, 2011, p.8

Systemic Racism Theory centres racism as foundational and historically prevalent within the US stating that it is, “engineered into its major institutions and organizations.” (Feagin and Elias, 2012). The discussion of a white racial frame that operates specifically as a meta-structure and the identification of ‘whites’ and ‘elite whites’ as units of analysis by Feagin and Elias (2012), building upon Critical Race theorists work, make clear that to identify the systemic racism within video games and gaming culture we must look at who holds positions of power and those roles’ connection to identity, ethnicity, and concepts of ‘race’.

The social construction of reality and power

In order to understand how we transfer racism from one reality to a virtual reality it is important to examine how power is socially constructed and applied. Using Berger and Luckmann’s (1991) ‘The Social Construction of Reality’, which states that there is a dialectical relationship between individuals and society related to the unification of Durkheimian objective reality and Weberian subjective reality, Dreher (2016) isolates its potential to analyse the construction of power. To understand how power itself is produced Dreher points to Bourdieu’s work (1990) on symbolic power and capital but takes it a step further stressing the importance of how belief in these types of capital is produced and maintained. The priming of individuals and the social narratives they live their lives in are “pre-figured by ideas, thought systems and categories prescribed by the ‘ruling class’ of a society.” (Dreher, 2016). By applying Feagin and Elias’s (2012) work on ‘whites’ and ‘elite whites’ as units of analysis to Dreher’s (2016) work on power we see the prominence that ‘elite whites’ hold in society and their ability to effectively distribute racist social narratives and structures, both consciously and unconsciously, to make up systemically racist institutions and structures.

Section 3: The Empirical Problem Stated

Who makes and plays video games and who can they play?

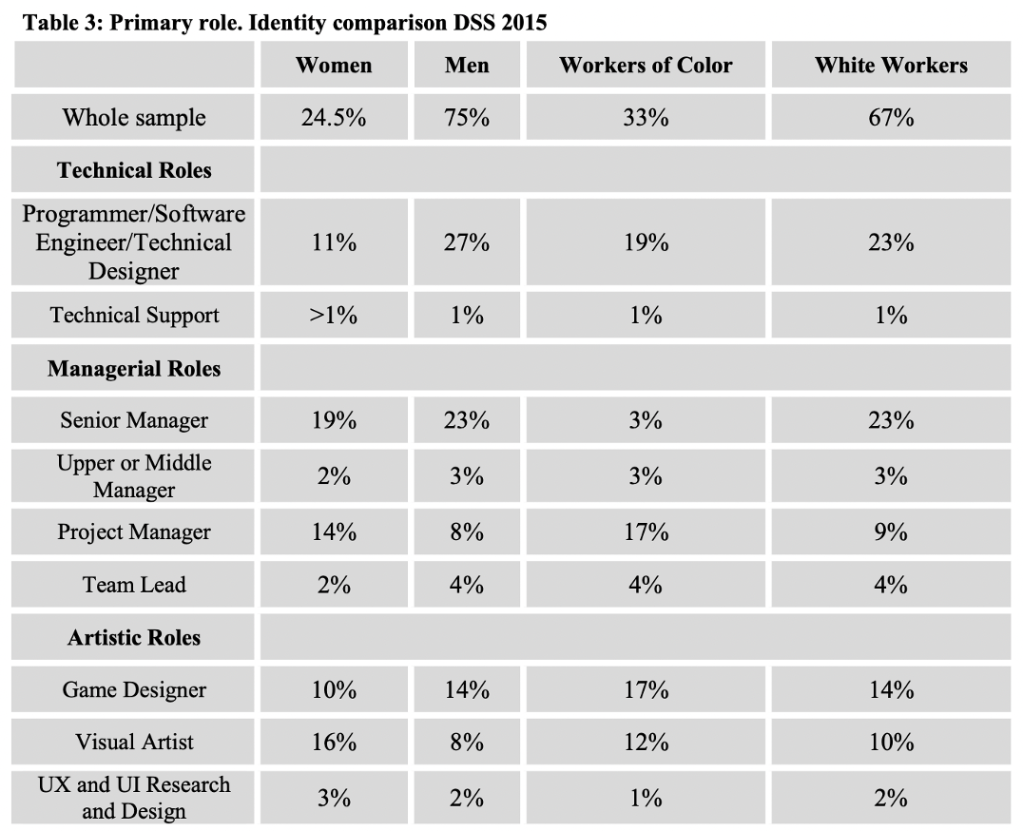

In the largest study (to date) of characters within video games Williams et al (2009) found that 82.9% of characters were white, 2.6% Latino, 11.4% Black and 2.6% Asian. The ethnic composition of the developer workforce at that time was 83.3% White, 7.5% Asian, 2.5% Hispanic, and 2% Black (Williams et al, 2009). When comparing the ratio of characters to developers both Williams et al (2009) and Gray (2012) highlight the importance of noting the prevalence, and often relegation, of black characters to sport focused games based on real life personalities rather than fleshed out characters with complex motivations and desires. A more recent report (igda, 2019) shows most developers identifying as White/Caucasian/European at 81% but 12% of this number also selected other ethnic categories, Hispanic/Latinx at 7%, Aboriginal/indigenous at 5%, East, South and South-East Asian at 10%, Black/African American/African/Afro-Caribbean and West-Asian at 2% (igda, 2019). When compared to the US census they found that, “the statistics for the DSS 2019 suggest a large overrepresentation of people identifying as white, and a slight overrepresentation of people identifying as Indigenous and as Asian.” (p.13, igda, 2019). This data outcome tracks with ideas that Williams et al (2009) put forward suggesting that there is a correlation between developers and the games they create rather than games accurately reflecting the population of the consumer market. In their 2015 report on primary roles and identities (see fig 1.) you can see the ratio of senior managers to ethnicity with 3% reporting as workers of colour and 23% reporting as white further highlighting the unbalanced relationship of positions of power and ‘race’ (Dreher, 2016). This issue can extend beyond developers to venture capitalists that are, “composed of ethnically homogenous teams” resulting in more diverse intellectual property (IP) being seen as “niche” or without a market (Peckham, 2020).

| Image Credits: igda, 2016. |

Why can’t black characters ride dragons?

It is important to acknowledge the hegemonic narratives at play that developers, whether consciously or unconsciously, use to situate players in the gameplay world. Kishonna L. Gray (2018) discusses this when looking at who constructs identity within gameplay saying that it is mainly created through the solipsistic lens of white masculine heterosexuality.

They go on to highlight several mediated narratives of blackness within gaming from the black man as criminal to the situating and dilution of black vernacular as ignorant and inferior to its white counterpart (Gray, 2018).

“When they add Black characters to a game they root them only in their real world context… why can’t Black characters ride dragons?”

Peckham, 2020

The meritocratic approach to narrative gameplay and its impact

The heavy lack of nuance, due to absent intersectional perspectives on society and our experiences within it, creates a space for players to reaffirm racist social narratives built from ideas of meritocracy in the virtual reality of video games (Crenshaw, 1991; Augoustinos et al, 2005). Christopher Paul (2018) addresses this when discussing the coding of meritocracy explaining that, “Video games celebrate and depend on a presumed social order based on skill and ability, even though the initial access points to video games are riddled with inequality.” (p.160). By engendering ideas around ‘fair’ and ‘balanced’ play being possible Paul notes that, particularly in western video games, “judgements of strangers were based exclusively on perceived ability… it drove evaluation based on a snap assessment.” (Paul, 2018, p.162). The structure of gameplay, and how it shapes and reaffirms players social narratives, shows a connection between ideas of erasing intersectionally complex experiences and the perpetuation of meritocratic myths within games.

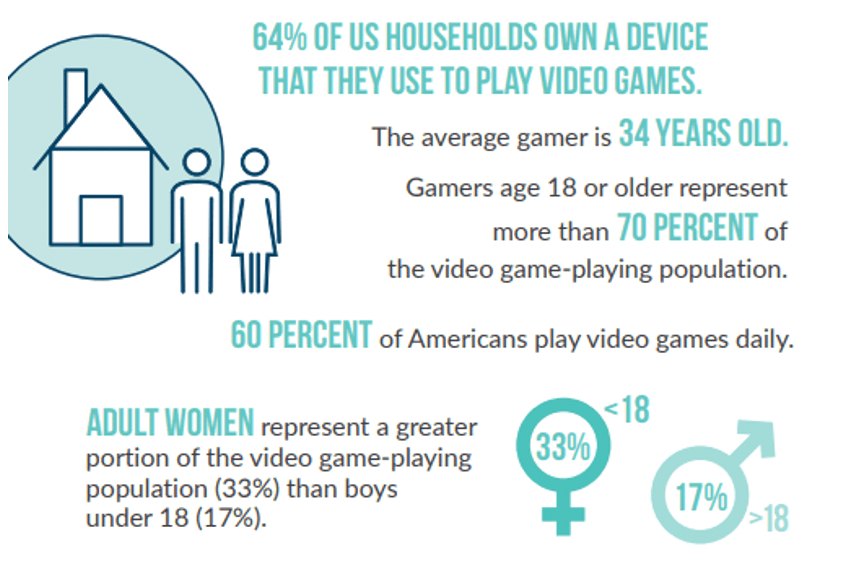

Privileged and deviant virtual bodies

The creation of video games in the image of developers allows for the transferral of systemic racism to virtual games and their social spaces which can be seen when the heavy weighting of developers as white and male is combined with the constructed ideas of the default gamer as young, white, and male rather than the reality (see fig 2.) (Gray, 2012; Theesa.com, 2018). Building on exposing the flawed ideas of how utopic and meritocratic video games are Gray (2012) points out that they are instead narratives of white centrality that position both masculinity and whiteness as normative and in focus while othering, and labelling as deviant, any expression of identity outside of these narrow fields.

| Figure 2. Image Credits: theesa.com, 2018. Source: Entertainment Software Association, “Essential Facts About the Video Game Industry,” |

This extends beyond gameplay itself to virtual community spaces where Gray links the discourse of ‘post-racial’ or ‘colourblind’ ideology to justify the use of racist language by white players (Gray, 2016, p.363; Gray 2018).

Section 4: Addressing the Problem

Representation matters

By understanding the correlation between representation in games to the developer workforce we can see the importance of managerial roles in the creative process and their impact on who has a voice and how it sounds within games and moderated communication platforms (Gray, 2018). When examining meritocratic and post-racial ideological oppression, through theoretical ideas on colourblindness, meritocracy and “mentioning” as a tool of white dominance, we can see how systemic racism is perpetuated in and around video games when the narrative is controlled by “whites” in positions of power (Chandler and Mcknight, 2009, p.225-227; Feagin and Elias, 2012). The call for developers to increase the diversity in their workforces has extended to diversity consultants for AAA games and slowly growing diversity in management positions. The impact of diversity can be seen by the consistent applied pressure from “diverse workforces” on hesitant management structures to speak out and address the Black Lives Matter movement with statements of solidarity and self-examination (Ayres, 2020). It can also be seen in the need for stricter diversity and inclusion policies present, not as an afterthought but, “through a game’s concept, preproduction and postproduction phases,” (Peckham, 2020).

New kinds of games

Video games have become a perfect way to systematically create belief in, and reinforce, social narratives around meritocracy and the ‘level playing field’ within gaming. To change this new games and approaches to gameplay need to be introduced and championed by the industry.

“New, different games can open up space for critical reflection and destabilising norms around merit in video games”

Paul, 2018, p.232

Christopher Paul (2018) discusses ideas around the power of empathetic gameplay and using video games to allow players to embody, at least for a limited time, other lifestyles and experiences that they would never be able to in the ‘real world’. They go on to present two solutions to traditionally meritocratic games: the first, introduce more instances of luck and outside factors that influence the players control over outcomes. This disrupts ideas of challenging work and skill growth being the only arbiters of fate in video games and encourages reflection and gratitude in gameplay resulting in an increase of empathy. The second, is to increase and diversify the traditional population of gamers which is already becoming more intersectional (Ruberg, 2020; Richard and Gray, 2018). Limited research has shown that the intentional cultivation of a positive community of players shifts the focus of everyday gameplay from who the best players are, and how to match them, to how to take part in a community (Paul, 2018).

An example of more cooperative gameplay is the use of Minecraft by researchers to examine intergroup bias between Palestinian-Israeli and Jewish-Israeli elementary school students and the impact of games on cognitive and emotional indicators (Benatov et al, 2021). They found that more research is needed to define whether it was the intergroup contact or cooperative aspects of the game which had a positive impact but confirm that cooperative gaming is, “not only priceless but required to help avoid further escalation [of intergroup bias].” (Benatov et al, 2021). However, sandbox games like Minecraft have been criticised for their neoliberal approach by perpetuating myths on “empire and capital” which encourage exploitation and expansion as development rather than domination (Dooghan, 2016). Again, pointing to the grafting of racist post-colonial ideas of resource entitlement onto virtual reality. This has caused some authors to suggest that diversity initiatives and consumer activism are not enough to counter institutionalised discrimination arguing that a stronger politically placed anti-capitalist stance is needed (Jong, 2020).

Section 5: Conclusion

In conclusion, addressing systemic racism within video games is not something which can, nor should be, done in isolation. The dialectical relationship between video games and society means that both have the power to shift and generate new social narratives and bring them to an audience which is growing in diversity. By diversifying development companies, investors, gameplay mechanics, and seeking a wider consumer base the gaming industry could not only effect change internally, but also, to have far reaching effects within society due to the reach of video games (Theesa.com, 2018).

References

Ayres, F. (2020) A temperature check of diversity and inclusion in the gaming industry. PCGamesn [online] 7 July. Available from: https://www.pcgamesn.com/game-industry-toxicity [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Augoustinos, M., Tuffin, K., Consalvo, M., and Every, Danielle. (2005) New racism, meritocracy and individualism: constraining affirmative action in education. Discourse and Society [online]. 16(3), pp. 315-340. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from:https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0957926505051168?casa_token=eWpVLiWTx5gAAAAA:wOPgmtJ27B_AbM38gtW2jXoE1bHiwCRA7f9U4We3Fu3lnOX1s2zjC_qotfz5T5JTIEOMA4hM6RR18Q

Benatov, J., Berger, R., Tadmor, C.T. (2021) Gaming for peace: Virtual contact through cooperative video gaming increases childrens intergroup tolerance in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology [online]. 92 [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103120304054

Berger, P.L. and Luckmann, T. (1991) The Social Construction of Reality [online]. London: Penguin. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: http://perflensburg.se/Berger%20social-construction-of-reality.pdf

Bourdieu, P. (1989) Social Space and Symbolic Power. Sociological Theory [online]. 7(1), pp. 14-25. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://voidnetwork.gr/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Social-space-and-symbolic-power-by-Pierre-Bourdieu.pdf

Chandler, P., McKnight, D. (2009) The Failure of Social Education in the United States: A Critique of Teaching the National Story from “White” Colourblind Eyes. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies [online]. 7(2), pp. 218-248. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: http://jceps.com/wp-content/uploads/PDFs/07-2-09.pdf

Crenshaw, K. (1991) Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review [online]. 43(6), pp. 1241-1299. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1229039?

Dooghan, D. (2016) Digital Conquerors: Minecraft and the Apologetics of Neoliberalism. Games and Culture [online]. 14(1), pp. 67-86. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1555412016655678

Dreher, J. (2016) The Social Construction of Power: Reflections Beyond Berger/Luckman and Bourdieu. Cultural Sociology [online]. 10(1), pp. 53-68. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1749975515615623

Entertainment Software Association (2018) 2018 Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry. Available from: https://www.theesa.com/resource/2018-essential-facts-about-the-computer-and-video-game-industry/ [Accessed 19 April 2021].

Feagin, J. and Elias, S. (2012) Rethinking Racial Formation Theory: a systemic racism critique. Ethnic and Racial Studies [online]. Symposium On Rethinking Racial Formation Theory: Issue 6, pp. 931-960. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/doi/full/10.1080/01419870.2012.669839

Fickle, T. (2019) The Race Card From Gaming Technologies to Model Minorities [online]. New York: New York University Press. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OkK1DwAAQBAJ&printsec=copyright&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Gray, K.L. (2012) Deviant bodies, stigmatized identities, and racist acts: examining the experiences of African-American gamers in Xbox Live. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia [online]. 18(4), pp. 261-276. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13614568.2012.746740

Gray, K.L. (2016) “They’re just too urban”: Black gamers streaming on Twitch. In: Daniels, J., Gregory, K., Cottom, T.M., ed. (2016) Digital Sociologies [online]. Bristol:Policy Press pp. 355-368. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316585614_They%27re_just_too_urban_Black_gamers_streaming_on_Twitch

Gray, K.L. (2018) Power in the Visual: Examining Narratives of Controlling Black Bodies in Contemporary Gaming. The Velvet Light Trap [online]. 81(Spring). [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://muse-jhu-edu.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/article/686904

igda (2016) Developer Satisfaction Survey 2014 and 2015: Diversity in the Game Industry Report [online]. international game developers association. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/21180408/IGDA_DSS_2014-2015_DiversityReport-2016.pdf

igda (2019) Developer Satisfaction Survey 2019 [online]. international game developers association. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://s3-us-east-2.amazonaws.com/igda-website/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/29093706/IGDA-DSS-2019_Summary-Report_Nov-20-2019.pdf

Jong, C. (2020) Bringing Politics Into It: Organizing at the Intersection of Videogames and Academia. PhD, Concordia University. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/986682/

Omi, M. and Winant, H. (1994) Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s [online]. London: Routledge. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=j9v6DMjjY44C

Paul, C.A. (2018) The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games: Why Gaming Culture Is the Worst [online]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Mip0DwAAQBAJ&lr=&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Peckham, E. (2020) Confronting racial bias in video games. TechCrunch [online] 21 June. Available from: https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/21/confronting-racial-bias-in-video-games/ [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Richard, G.T., Gray, K.L. (2018) Gendered Play, Racialized Reality: Black Cyberfeminism, Inclusive Communities of Practice, and the Intersections of Learning, Socialization, and Resilience in Online Gaming. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies [online]. 39(1). [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://muse-jhu-edu.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/article/690812

Ruberg, B. (2020) The Queer Games Avant Garde. London: Duke University Press [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=T5XUDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT4&dq=video+games&ots=HDxx3z7plU&sig=0rguauQR2jPf_R9iEbbQ1vvD6Kg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=video%20games&f=false

Stefancic, J. and Delgado, R. (2010) Critical Race Theory: An Introduction [online]. Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_working_papers/47

Williams, D., Martins, N., Consalvo, M., and Ivory, James. (2009) The virtual census: representations of gender, race and age in video games. New Media and Society [online]. 11(5), pp. 815-834. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444809105354?casa_token=Fi2Y3JjQUxYAAAAA:1UbjuodgTJNOjL0sT1Aekx91qlUdgbQwprsonCq_rHQ28QWHeKvJFSzbWcjCkqamwta34Fvif4V6gw

Winant, H. (2000) Race and Race Theory. Annual Review of Sociology [online]. 26, pp. 169-185. [Accessed 17 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/223441?seq=1

Second Year Undergrad